The Story of Food

Not so long ago, say in the early to mid-1990s, if you drove down Sheikh Zayed Road towards old Dubai, there was only one point of reference. One landmark, like a desert lighthouse, that would signify you’re fast approaching your destination in Bur Dubai, Dubai Creek or Deira. The World Trade Centre.

Almost there, you’d have already driven along Umm Suqeim and Jumeirah on your left, past the empty expanse of sand where Burj Khalifa would punch the sky over a decade later to your right and onto a deserted stretch that today bisects one of the world’s most famous skylines.

Back then it was just desert road. But if you took a left at the World Trade Centre roundabout and headed down Al Dhiyafa Road, slowly a hive of activity emerges.

Among the low-rise buildings, if you look to your right, you’ll find Al Mallah restaurant, a bona fide Dubai institution. It has, of course, been around for far longer. Since 1979 in fact, when the Emirates had been an independent country for no more than eight years.

Not much has changed in the old cafeteria after all those years. Those large fruit cocktails. Zaatar manakeesh. Fresh falafel. A bit of hummus. And of course those famous shawarma sandwiches.

Anyone who’s ever lived in Dubai over the last two decades will likely have an embarrassing story about a desperate, after-hours dash towards Al Mallah. “We’ll take whatever you have left”.

Today, it is still going strong, though Al Dhiyafa street is a somewhat livelier avenue, by day or night.

Alongside Al Mallah, you’ll find many copycat cafeterias and sandwich shops displaying those revolving beef and chicken stacks. And among the traditional sandwich shops, increasingly over the years, are fast food joints like KFC, Pizza Hut and Hardee’s.

But take a short walk to the small back roads of this strip and you’ll find a whole new world of smaller cafeterias that offer even cheaper food, from sandwiches to Bahraini grills and seafood dishes. Every taste is catered for it seems.

It’s a scene repeated in neighbourhoods across the seven Emirates.

From Abu Dhabi, all the way up north through Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman, Umm Al Quwain and Ras Al Khaimah, and west to Fujairah, neighbourhood hole-in-the-wall food outlets established by Emiratis, Middle Easterners and Asian expatriates are as close to what we can call local food as is possible in this land of almost 10 million people.

Some of the country’s most beloved food outlets have had the most humble of beginnings, with some having origin stories that have gone down in legend.

In the late 1960s and early 70s, as Abu Dhabi was taking its first steps towards becoming the metropolis it is today, Sheikh Zayed Bin Sultan Al Nahyan would drive his Mercedes down the future Corniche to keep a watchful eye over how the different parts of town, including the Khalidiya, were coming along.

There, a young Palestinian man by the name of Radwan Al Tamimi, who ran a small mobile kiosk near what today we call the breakwater, would every day provide Sheikh Zayed with fresh juice as the country’s founding father would take break from the scorching temperatures.

The 17-year-old’s kindness was not forgotten, and with the help of Sheikh Zayed, he ended up opening a seafood restaurant that bore the nickname that the UAE president had bestowed on him.

Bu Tafish.

These days, with several branches in Abu Dhabi and Dubai, the name is a byword for unrivalled traditional seafood dishes of this land, the Gulf and the wider region, beloved by residents and any tourist lucky enough to stumble across it.

There are others.

Ask any Dubai resident to recommend a hole-in-the-wall gem beyond all the glitzy restaurants and there’s a very good chance the response will be the Indian and Pakistani food outlet Ravi’s, established in 1978 by Chaudary Abdul Hameed. Never mind a favourite hidden gem, for many Ravi’s is quite simply the city’s best restaurant. A quick taste of their curry or chicken Tikka is usually all it takes to corroborate that opinion.

The Emirates today is quite unrecognisable from the country that bred Bu Tafish, Al Mallah and Ravi’s. Imitators, some worthy and others less so, saturate the old and new neighbourhoods.

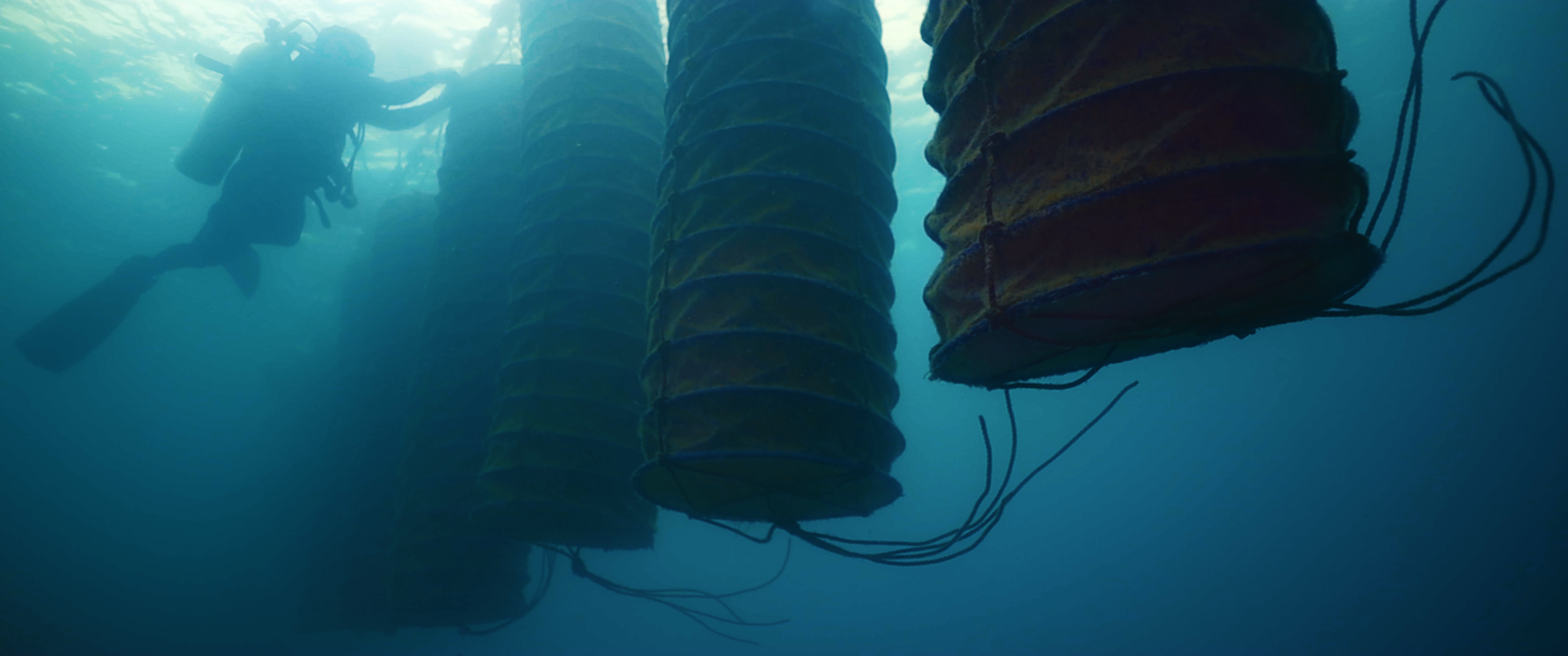

Bu Qtair on Jumeirah Beach Road, with its fresh catch of local favourite hammour or shrimps ready to grill has for one already attained cult status, while there are the more upmarket Ibn Al Bahar on Palm Jumeirah, or Fish Beach Taverna at Le Meridien Mina Seyahi. Meanwhile, shawarma restaurants are now more like fast food shawarma chains, offering modern, and often wild, takes on a classic recipe that didn’t really need any tinkering with in the first place. And you don’t really need to look too hard to find a curry house or two.

The UAE is often called a melting pot, a label as cliched as it is true. Two hundred nationalities, living side by side, each adding its own culture, language and quirks. In truth, that doesn’t always lead to a comfortable mix.

Thankfully, blurring the boundaries has often come through a collective love of food. But first time visitors asking for a “traditional or local” meal are very often met with a resigned shrug by residents.

While local Emirati cuisine consists of biryani or machboos dishes of chicken, meat or fish with rice, or Harissa, the sheer number of other cuisines can leave you confused.

It’s not always easy to stand out in an almost saturated food industry in the Emirates, from the top of the literal and metaphoric food chain, down.

In Abu Dhabi, Yas, Reem, Al Maryah and Saadiyat have become literal islands of the fine cuisine outlets, steakhouses and bars.

Likewise in Dubai, there are the aspirational spots in DIFC such as Zuma, Cipriani, La Petit Maison, Gaucho and many others, as well as the seemingly never-ending supply of new brands that launch, and others that shut down, on a weekly basis. Elsewhere, Dubai Marina, JLT, Palm Jumeirah and City Walk have emerged as their very distinct hubs.

Just below that tier, the competition to distinguish your brand from the competition is particularly messy. Cue the more boutique offerings.

Every street corner seems to have its own independent burger joint - the more alternative, the better. The experience of having a burger at, say, Salt on Kite Beach bares little resemblance to chomping on a Big Mac or Whopper.

Certainly more and more restaurants are now located on beach fronts, as if owners and developers have wisened up to the fact that in a country with such long stretches of beaches and decent, outdoorsy weather for long periods of the year, it is borderline negligent not to count, and exploit, these blessings.

Some business owners go the extra mile, like Dubai resident Hatem Mattar who after an inspiring trip to Texas in 2014, launched Mattar Farm, the city’s first brisket smokehouse. Or British expatriate Ramie Murray, who flew against conventional wisdom, and marketing advice, to set up a successful oyster farm in Fujairah.

Coffee shops too have veered towards the artisanal. The 1990s and 2000s may have seen high-street brands like Starbucks and Costa Coffee redefine the coffee-drinking experience, but over recent years there has been renewed appetite for quality over mass consumerism.

Jam Jar and Nightjar in Al Serkal Avenue, Alchemy on Al Wasl Road, and the five branches of % Arabica across the city are just a few of the more popular coffee houses that have established themselves in Dubai. And then there are the more specialised roasters that import high quality beans from all over the world, such as Cypher, set up by long-time UAE residents Mohammed Merhi and Sami Sehweil, and Boon Coffee, launched by Orit Mohammed.

“Coffee is in my DNA, as a Harari girl from Ethiopia, it’s part of our culture,” Ms Mohammed said “Dubai is a mini-world, you have so many people with so many backgrounds, it evokes memories for a lot of people.”

She admits that when she launched her roastery in Dubai she had no significant business network to speak of, and did not fit into the stereotype of modern-day, coffee-producing hipsters. With no experience, and not even a single tattoo in sight, she had to learn the trade, and earn the trust of clients, as she went along.

“I think Dubai expedited my success,” she said. “It’s such a small community, when people heard how good the coffee was, it was easier for big doors to open.”

Those doors opened not just for her.

From a shawarma hole-in-the-wall or beach-facing seafood shack, to a burger joint or a fine cuisine restaurant. If you have an idea and some cash to splash, it seems the food business is always welcoming for the residents of the UAE.

It doesn’t always work out. But if it does, and you’re lucky enough, you just might, in 40 years’ time, be held in the same esteem as Bu Tafish, Al Mallah and Ravi’s.

That’s food for thought.